I’m serious…stop doing it.

If you never let your singers just sing through minutes or whole pieces of unrehearsed music, then you may not even need to read on. However, if you do, please consider the following.

We already know that with every repetition, notes and rhythms in any piece become easier for a singer. Repetition can and should be a key tool for every choir director in the world. In a recent Wall Street Journal article on “Why Tough Teachers Get Good Results”, the second major point is that repetition can be very valuable and other countries continue to get this while the U.S. has vilified it.

However, with that power comes great responsibility (thank you, Spider Man). Every time you “run through” sections a new piece and pay no attention to phrasing, vowels, dynamics, text stress, articulation, and tone, you ingrain the status quo a little bit more. A singer who has a tendency to use diphthongs on every word ending in “Eh”? Get ready for him to use those more next time you sing that section. Another singer has a pressed tone and tries to overpower the other altos in a quest for part supremacy? Get ready for her to be worse with each unchecked repetition. My friend and colleague Brody McDonald has a great blog post on this.So if rehearsing large swaths of music with no other instruction is bad, what is better?

Start with individual phrases, 4-16 measures depending on the ability level of the choir and the difficulty of the music. The more challenging the literature for the ensemble, the less music you should try at once.

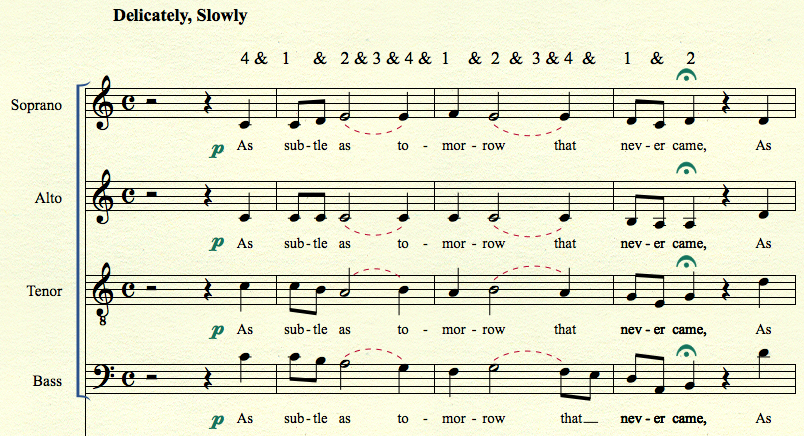

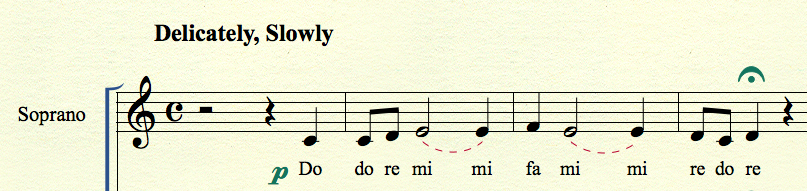

Take my “About My Dreams” for SATB choir. My particular high school choir would not have problems with the simple rhythms contained in this phrase, but if yours would, then you may want to start by counting the rhythm using the method of your choice (1e&a, takadimi, etc.).

In the opening phrase, I would probably start with solfege since the piece is diatonic and stepwise (with the exception of the bass). While one section sings the solfege out loud, others can be silently practicing with Curwen hand signs, writing in the solfege syllables, or audiation.

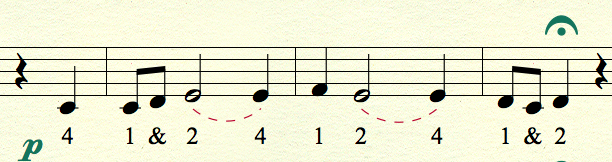

Add musical detail immediately. I would start this process using count-singing for two reasons. First, this piece is in English and allowing non-professional choirs to sing in English unchecked often leads to regional diction issues. Secondly, it is very nuanced and requires careful phrase shaping and text stress. Count-singing was a staple of American choral icon Robert Shaw and basically consists of singing the notes on the beat counts plus the off beats:

The power of count singing lies in the ability to shape the phrase and add articulation. The very first time I taught this phrase, I would model the following:

Decrescendos, often one of the toughest things for choirs, become much easier when taught and reinforced through count singing.

Now that we have sightread the rhythms and notes and have done count singing, we would then speak the phrase in rhythm with impeccable diction and pure vowels. This should also include the dynamics and articulations already reinforced above.

Remember that for this measured process to work, you must ensure its success with repetition at each phase of learning.

Now that you’ve done the count singing and the diction in rhythm, it is time to combine them, singing the full phrase on text, with musical details. You’ll be surprised at how consistently your choir will sing this phrase every time you come back to it!

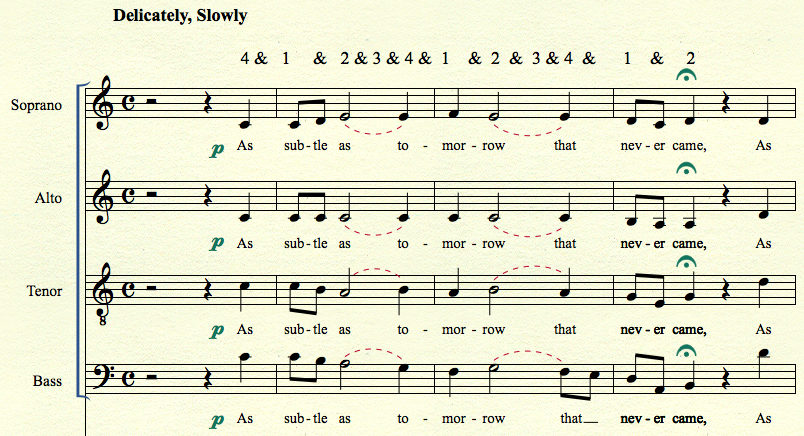

For those of you who are saying to yourself, “this sounds great, but I don’t have that kind of time in my rehearsal,” consider that you are going to get a valuable return on investment for having done this process. Look at the next phrase of the piece:

That’s right, different notes, same rhythms– you can immediately apply everything you just did to this phrase, and it will take a fraction of the time. It may even happen on the first read through after solfege. Listen and look through the whole piece to find that you’ll get to reap the rewards of this measured, focused process two more times.

So please– stop running through unrehearsed music! Your choir may beg for it (“let us sing the rest”, “can we please just run it all the way through” etc.), but you have to hold strong. The reward for them will be much greater when the run-through is musical, metrically accurate, nuanced, and in tune. Once you get these aspects set on music, then use varied repetition as your best friend. My saying is “Repetition leads to competence, and competence leads to confidence.”